from….http://hempology.org/JD%27S%20ARTICLES/BOSTHIST.html

THE HUB’S HEMP HISTORY

By John E. Dvorak, Hempologist

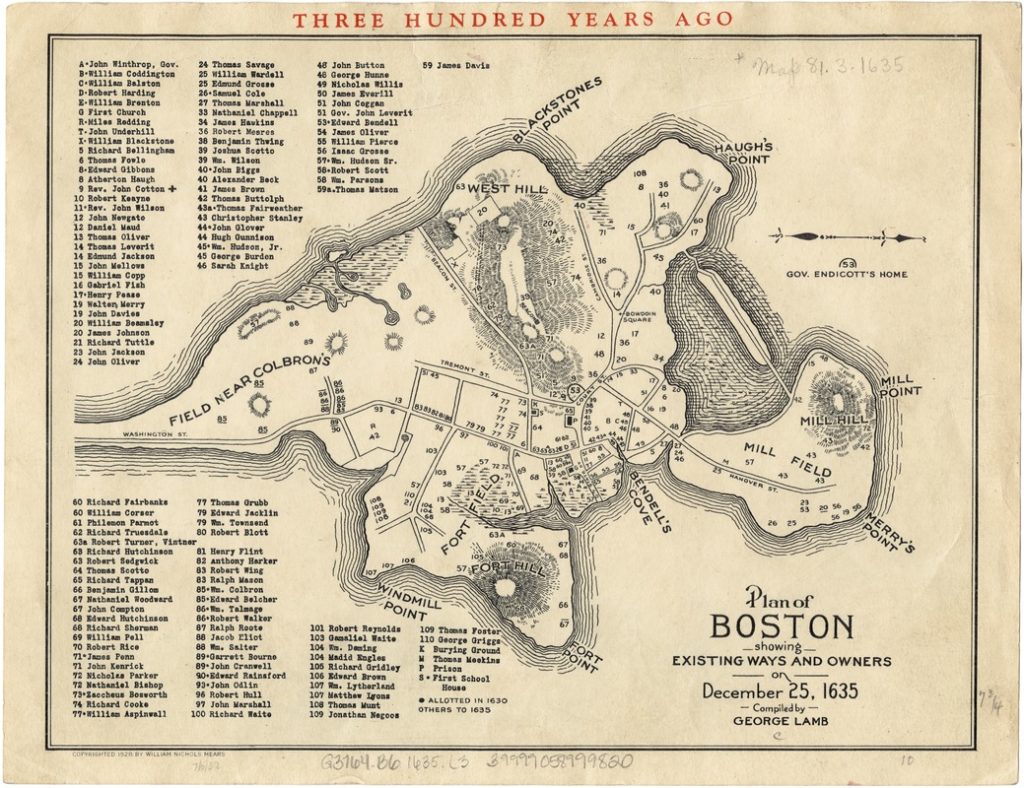

Built on isolated Shamut peninsula with only Boston Neck connecting it with the mainland, Boston truly was the hub of the universe for many of this country’s first immigrants. Shipyards and cordage factories (ropewalks) were needed to supply this thriving port with its means of transportation, commerce and defense. Many ships built in America using Russian hemp spent much of their useful lives sailing from the New World, bringing home iron and hemp to fulfill the needs of future fleets.

1630 marked the first year that hemp cordage was made in Boston. While hemp was planted in nearby Salem a year earlier, it is most likely that the actual fiber used by the Boston ropewalks (then and for many years to come) came from abroad. In 1641, several Bostonians convinced John Harrison, a ropemaker from Salisbury, England, to set up shop in Beantown. Harrison found ample room for his cumbersome ropewalk at the foot of Summer Street, near what is today South Station. For over twenty years, Harrison enjoyed a virtual monopoly in Boston’s ropemaking business as evidenced by a 1663 order from town authorities demanding that a fellow twine twister, John Heyman, stop making rope and leave town. Harrison’s competitive advantage ended when he died, and the number of ropewalks increased.

Throughout the 1700’s, subsidies were given to farmers to encourage the cultivation of hemp and the manufacturing of cordage and canvas. Indeed, at various times, one could pay their taxes with flax, tar, leather, and hemp. However, most hemp used for naval purposes was imported. This is evidenced by the following facts:

· During the first six months of 1770, the colonies imported over 400 tons of hemp from Great Britain;

· America’s annual imports of hemp rose from 3,400 tons around 1800 to nearly 5,000 tons between 1820 and 1840;

· Each year between 1839 and 1843 the Charlestown Navy Yard processed an average of 500 tons of Russian hemp but only 7 tons of American grown hemp.

In 1722, Boston’s 12,000 inhabitants made it the largest city in British North America. Captain John Bonner’s map from this era documents the location of six ropewalks (1722 CAPTAIN BONNER’S MAP OF BOSTON). These wooden buildings, which made marine cordage with tar and hemp, were unfortunately severe fire hazards. Their proclivity to burn necessitated the need to locate these peninsular appendages in sparsely populated or swampy areas.

Several ropewalks were built on or near Barton’s Point. This is the area between what is now the State House and Mass General Hospital (1796 NEAR THE BOSTON COMMON, CAMBRIDGE STREET AND LEVERET STREET ). Another group ran along Pearl Street, now Post Office Square in the middle of modern day Boston’s financial district (1777 MAP OF BOSTON). By 1794 there were fourteen ropewalks in Boston and over 150 scattered across America (173 in 1810) . The ropewalks on Pearl Street remained until July 30th, 1794, when a fire destroyed much of the neighborhood from Milk Street to Cow Lane (now High Street).

At this time the towns-people of Boston made a far reaching decision by granting the rights for the construction of new ropewalks on the “remote” marshy flats of the Charles River at the foot of the Boston Common. This gift was made with the condition that the grantees build a sea wall to protect the land. The end result of this civic minded philanthropy turned the Back Bay from a formidable body of water into a fashionable place to live. For the next thirty years, the ropewalks built on the site of the Old Round Marsh created the cordage that equipped the ships that shaped this country. However, by 1824, the Back Bay was shaping up too and Mayor Quincy convinced the town to spend the significant sum of $55,000 to re-acquire the land, clearing the way for the creation of one of Boston’s most treasured jewels, the Public Garden.

The need to locate cordage factories away from heavily populated areas certainly helped the Plymouth Cordage Company, which was founded in 1824. During the first half of its 125 years of business, cannabis hemp was the raw material used in one of the largest cordage factories in the world. Portions of it have been restored and named Cordage Park where you can shop, have dinner, and enjoy several ropemaking exhibits and artifacts. A portion of one of their original ropewalks has even been moved to the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut.

In 1837 a steam powered ropemaking complex was completed at the Charlestown Navy Yard that would manufacture most of the U.S. Navy’s cordage until it was closed in 1971. Designed by Alexander Parris, better known as the architect of Boston’s Quincy Market, this historic facility includes a tar house, a hemp house, and America’s only remaining full-length ropewalk, a stone structure stretching one quarter of a mile long. Even during the Navy Yard’s tough times in the 1880’s the ropewalk provided constant work. The nascent equal rights movement benefited during both World Wars when women were employed as ropemakers. When the U.S.S. Constitution was virtually rebuilt from 1927 to 1931 the ropewalk was still able to manufacture the ancient-style four stranded hemp shroud-laid cordage required for her standing rigging. Charlestown’s ropewalk is now slated for restoration. Tall ships could once again be rigged with hempen cordage made in this horizontal monument that literally and figuratively lies in the shadow of Bunker Hill and Old Ironsides. While perhaps not as familiar as other cultural icons (yet!), ropewalks are nevertheless enduring symbols of hemp’s role in this country’s national security, defense and prosperity.

[1] Boston’s Workers: A labor History

James R. Green & Hugh Carter Donahue

1979

[1A] page 4

The town’s decline began with a terrible smallpox epidemic in 1721, which recurred in 1730, killing almost two thousand citizens – “a blow from which the town never really recovered,” according to G.B. Warden. “Ship captains and farmers avoided the town as much as possible during the epidemics and found that they could get better prices and services in other Massachusetts towns.” In 1734 Parliament passed a law limiting the colonial distillers’ supply of cheap French molasses. “Shipwrights, coopers, caulkers, sailors, carpenters and ropemakers suffered along with the distillers and did not even have the consolation of cheap rum to drown their sorrows,” Warden comments. “By 1740, orders for new ships from the Boston yards had dropped from forty to twenty a year; shipbuilding, fishing, distilling and related trades declined by 66 per cent in total business.” Boston had lost its status as the leading port in the colonies.

[1B] page 5

[Illustration of ropemaking]

=-=-=-=-=-

[2] History of Manufactures in the United States

Volume I: 1607-1860

Victor S. Clark

W. Farnam. New York, P. Smith, 1959

[2A] page 24-25

Therefore in 1705 an act was passed granting a bounty of 6 pounds a ton on hemp. These acts were continued with some modification for half a century. They promoted the production of the commodities to which they applied. But the industry remained in a degree artificial and whenever British encouragements were relaxed the colonists reverted to lumbering and homespun industries. The bounty on hemp and flax could hardly have deprived colonial manufacturers of their raw materials, by causing them to be transported to England; for hemp in large quantities was imported from Europe by colonial rope-makers six years after the last bounty upon that commodity was granted by England. It is safe to assume that these fibers were not largely exported when the local demand was sufficient to cause what were for the time extensive importations.

[2B] page 33

After the British government subsidized naval stores from America, some colonial flax and hemp bounties were intended to foster the production of those commodities for British use, and therefore directly to affect agriculture rather than manufactures. But except in a few of the planting colonies, the local market continued to absorb most of these products; so that in spite of the artificial inducement to export, the resulting increase in raw materials was a benefit principally to colonial tradesmen.

[2C] page 34

About 1700 Massachusetts had an act on its statute books “to encourage the sewing and well manufacturing of hemp,” and compelled local cordage-makers to use hemp raised in the province.

Hemp was never exported extensively to England, even when the bounty was highest, and though burdened with British duties and extra freight, it was imported in considerable quantities from Europe by New England rope-makers.

[2D] page 36

In 1734 Connecticut offered a bounty of 20 shillings for every bolt of “well wrought canvas or duck, fit for use, of thirty-six yards in length and 30 inches wide, and weighing not less than 45 pounds, made of well-dressed, water-rotted hemp or flax.”

[2E] page 39

In 1701 the same colony [Mass.] passed a law subsidizing a company to the extent of a farthing a pound for all the hemp it purchased, subject to the condition that the company buy all “bright, well-cured, water-rotted hemp, 4 feet long,” raised in the colony, for 4.25 pence a pound.

Again in 1727 Massachusetts, in extension of the general bounty of 20 shillings a bolt upon duck already established by the act of the previous year, granted to John Powell a subsidy of 30 shillings a bolt for ten years; and six years later the same encouragement was given to Obediah Dickenson, of Hatfield, who was also manufacturing this article. Duck bounties were retained in New England for some time after the Revolution.

[2F] page 45

At various times Massachusetts and New Hampshire made flax and hemp, tar, turpentine, leather, and oil receivable for taxes.

[2G] page 82

Hemp grew better in the warmer climate and stronger soil of Pennsylvania than in New England, but on new ground was raised successfully as far north as Maine. Its chief centers of cultivation were the same as those of flax [Merrimac and the Connecticut valleys], but the latter was raised more generally and distributed more widely. Hemp was in part a commercial crop, while flax, so far as it was raised for fiber, supplied principally household consumption.

[2H] page 112

The colonies were purchasers as well as sellers of raw materials. During the first half of 1770 Boston imported from Great Britain between 400 and 500 tons of hemp.

[2I] page 326

Although in colonial days the British Government paid bounties on American hemp, our rope-walks, as previously observed, even then used imported materials. Neither Federal duties nor the conditions of non-intercourse were at first more successful than these earlier bounties in freeing the country from foreign dependence for this commodity. Our imports slowly rose from about 3,400 tons a year before 1800, to 4,200 tons during the second war with England, and to a maximum of nearly 5,000 tons between 1820 and 1840.

=-=-=-=-=-

[3] Boston; A Topographical History

Walter Muir Whitehill

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

1959

[3A] page 33

Past Wind Mill Point, Hill’s Wharf projects into the South Cove. Behind the wharves is ample space even for ropewalks, which are cumbersome things at best. A maritime community needs cordage; indeed John Harrison, a ropemaker, was plying his trade in the South End at the foot of Summer Street as early as 1642. Bonner’s map shows three ropewalks west of Fort Hill, in the area that would now be between Congress and Pearl Streets, with others on the unsettled land behind the Trimountain.

From the ropewalks, Cow Lane (now High Street) leads southwest into Summer Street a little below Church Green, where at the junction of Blind Lane (now part of Bedford Street) a New South meeting house had been built in 1716. Summer Street, between Church Green and Marlborough Street, long remained a pleasant and uncrowded place to live.

[3B] page 37

If one had no other documents on colonial Boston, the crowded shore line of Bonner’s map alone would testify to the maritime nature of the place, for a town of twelve thousand inhabitants with upwards of forty wharves, more than a dozen shipyards and six ropewalks, could only be a thriving seaport. It was, of course, not only that but the largest town in British North America – a place that it continued to hold until the middle of the eighteenth century, when it fell behind the faster growing ports of Philadelphia and New York.

[3C] page 48

One notes, however, that most of these products are either for or from the sea. Ropewalks had been a familiar feature of the remoter parts of the town almost from the beginning, but in 1789 a duck manufacture for the production of sail cloth was established, with the assistance of the General Court, near the Common in Frog Lane.

[3D] page 55

one of Boston’s periodic fires opened the way for a complete change in an adjoining part of the South End. When the ropewalks between Pearl and Atkinson Streets (1777 MAP OF BOSTON) burned on 30 July 1794, the townspeople (in the words of Dr. Shurtleff) “opened their hearts, though they closed their senses: by granting the marshy flats at the foot of the Common for the erection of buildings to replace those destroyed. This gift, which consisted of part of the area that is today the Public Garden, was made upon condition that the grantees erect a sea wall to protect the land – thus beginning the encroachment upon the Back Bay – and that no ropewalks be again built on the old sites. Spontaneous emotional generosity in town meeting is dangerous, for it often – as in this case – secures a temporary advantage at the expense of the future. In 1794 the flats at the foot of the Common seemed a remote spot, admirably adapted to ropewalks. Thirty years later, when Boston was beginning to grow toward the west, it cost the townspeople fifty-five thousand dollars to recover the land so cheerfully voted away in 1794.

Across High Street Jeffrey Richardson, owner of one of the destroyed ropewalks, built himself after the fire a square, three-story house that was soon overshadowed, in 1800, by Jonathan Harris’s more ambitious house on the opposite corner.

[3E] page 98

Boston also owes its Public Garden to Mayor Quincy’s foresight. We have seen how in 1794, out of a mixture of sympathy for the unfortunate and a desire to get an unsightly nuisance into a remote spot, the town had imprudently granted limited and qualified rights to the flats at the foot of the Common for the construction of ropewalks. Thirty years later in February 1824, when the site so cheerfully granted away was no longer remote, the city regained this land by paying the occupants the large sum of $55,000. With a marked difference of opinion among inhabitants about the future of the tract, Mayor Quincy submitted the problem to a general meeting of the citizens on 26 July 1824, which overwhelmingly sustained the view that the land now comprising the Public Garden should be annexed to the Common “and forever after kept open and free of buildings of any kind, for the use of the citizens.”

=-=-=-=-=-

[4] The Book of Boston: The Federal Period 1775-1837

Marjorie Drake Ross

Hastings House Publishers

1961

[4A] pages 23-24

Fourteen ropewalks produced the ropes for the many ships. These narrow wooden boardwalks, or roofed sheds with open sides, stretched out in long, straight lines. Myrtle Street on Beacon Hill originally had three ropewalks running from what is now Grove Street to Hancock Street. Others were on the site of the present Pearl Street, on the opposite side of the town, until they burned down. In 1794 the marsh along the water front west of the Common was filled in for a new ropewalk. This remained in use until 1824. Later the area became the Public Garden.

=-=-=-=-=-

[5] Commonwealth History of Massachusetts, Volume 4 (of 5)

Edited by Albert Bushnell Hart

The States History Company

1927-28

[5A] pages 39-40

CORDAGE AND SAILCLOTH

Anybody knows that a ship cannot be operated without sails and rigging. Despite a prejudice in favor of imported canvas, repeated efforts were made to establish sailcloth factories in this country to supply the requirements of the shipbuilding industry. Flax and hemp were cultivated in the valleys of the Connecticut and the Merrimac, and in 1788 a sailcloth factory was established in Boston. The 800-ton Massachusetts was supplied, about 1790, with sails and cordage made in Boston. There was some difficulty in securing competent labor, however, and even with the encouragement of various bounties this and a number of similar enterprises on a more modest scale were unsuccessful.

Hemp seems to have been planted in Salem in 1629 and a rope walk was constructed in Boston the same year. Other manufactories of cordage were established in the colony, and although the industry has never been largely productive and profitable it was important; and its development is to be traced to those factors which gave rise to the shipbuilding industry, to which it was a necessary adjunct.

=-=-=-=-=-

[6] The Story of Rope

The History and the Modern Development of Rope-Making

Compiled and published by Plymouth Cordage Company

1916

[6A] page 19-21

It is recorded that rope was made in Boston as early as 1641 or 1642. John Harrison, a rope-maker of Salisbury, England, came to this country at the request of a number of citizens of Boston, and set up his business in that village. He seems to have had a monopoly of the local trade for a good many years, under the paternal protection of the town authorities, for John Heyman, to whom permission to make rope in Boston was given in 1662, was the next year ordered to give up the work and depart from the town, it being found that this competition interfered with Harrison’s business to such an extent as to make it difficult for him to properly support his family of eleven persons.

However, upon the death of Harrison this monopoly came to an end, and ropewalks began to multiply in Boston as well as in other parts of the country. In 1794 there were fourteen large ropewalks in Boston, the business having steadily increased with the development of the new country. The importance of this industry is shown by the report that in the federal procession in Boston in 1788, the rope-makers outnumbered any other class of mechanics.

In 1810 there were 173 ropewalks in the United States, scattered over the country from Maine to Kentucky.

=-=-=-=-=-

[7] Topographical and Historical Description of Boston

Nathaniel B. Shurtleff

Noyes, Holmes, & Co.

1872

[7A] page 121

That portion of the town lying west of the neck and of the Common, and which for many years has been known as the Back Bay, might well have been called the West Cove. In 1784, this part of the town, now making such rapid progress as the region of stylish and comfortable private residences, was entirely destitute of houses, and no streets had been laid out west of Pleasant street and the Common. The first improvement in this direction may be said to have commenced at the laying out of Charles street in 1803, and when the Western avenue enterprise, incorporated on the fourteenth of June, 1814, was undertaken, and the causeways and dams running to Roxbury built and the water shut out of the receiving basin. The removal of the ropewalks west of the Common, in 1823, aided also in this great work. Boylston street was soon afterwards extended west, and on the twenty-sixth of October, 1837, the Public Garden was laid out by the city.

[7B] page 135

“11. From the South corner of Rawson’s Lane down the common, as far as West Street, thence running down the North side of Pond street and Blind Lane into Summer Street, thro’ Barton’s Rope Walk as far as Mr. Hubbard’s thence up the Hill, and then down Cow Lane, the South East side into Summer Street, and then the Southerly side of Summer street, thence crossing over and taking the Westerly side of Marlborough Street as far as Rawson’s Lane, including the South side of said Lane.

[7C] page 312

On the west side of the Common was the low marshy land bordering upon the water, on part of which was Fox Hill, and on the flats of which in later days stood the five rope-walks, which the elder Quincy, in the first years of his mayoralty, removed with such marked improvement to the neighborhood.

[7D] page 355

CHAPTER XXVI. Public Garden

Land Granted and Ropewalks built in 1794 . . .

The Public Garden was originally part of the Common; but a great fire occurring in the neighborhood of Pearl and Atkinson streets, whereby the seven old ropewalks were burnt on the thirtieth of July, 1794, the towns-people opened their hearts, though they closed their senses, and resolved to grant the flats at the bottom of the Common for the erection of six new buildings in place of those destroyed, on condition that no more ropewalks should be built between Pearl and Atkinson streets upon the old site. This rash act of our fathers fairly lost to the town the old Round Marsh, which had always, from the first settlement of the town, been a part of the Common or Training Field;

=-=-=-=-=-

[8] Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914

W.H. Bunting

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

1971

[8A] page 440

[description of figure 10.5] A view of a portion of the interior of the Navy Yard’s magnificent ropewalk. When the frigate Constitution was virtually rebuilt in Dry Dock Number One from 1927 to 1931 the ropewalk was still able to manufacture the ancient-style four stranded hemp shroud-laid cordage required for her standing rigging – occasionally navy yard conservatism is fortuitous.

[8B] page 441: [figure 10.5]

=-=-=-=-=-

[9] Currier, History of Newburyport, Volume I

[9A] page 102

[on July 30, 1794] a disastrous fire destroyed seven cordage manufactories and many shops and dwelling houses between Milk Street and the west side of Fort Hill, in Boston.

=-=-=-=-=-

[10] James Henry Stark’s Antique Views of Boston

Burdette & Co., Inc.

1967

[10A] page 18

Drawing of view of Boylston St. from Tremont to Carver as it appeared in 1800.

[10B] pages 34-35

1722 map of Boston by Captain John Bonner

=-=-=-=-=-

[11] America, Russia, Hemp, and Napoleon – American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783 – 1812

Alfred W. Crosby, Jr.

Ohio State University Press

1965

[11A] page 22

Soon after the Revolution, New England was again trying to subsidize the domestic production of sailcloth, but with no more than the usual results. A Boston canvas manufactory in 1791 did not earn 1 per cent profit above the bounty received from the state. Similar factories existed about this time . . . but they all, Boston’s included, had failed by 1795.

[11B] page 56

Of the thirty American vessels that cleared St. Petersburg in 1793, twenty-one had New England ports for destinations: ten for Boston, five for Salem, three for Providence, two for Newburyport, and one for Gloucester. The remaining nine comprised seven for Philadelphia and two for New York. In 1810, there were sixty American vessels in the port of Archangel. Fifteen of these were from New York – more than from any other single port – but a full half of the sixty came from the hundred miles of coast between Boston and Portland.

Massachusetts led all the states involved in the trade with Russia. She did so not because of the predominance of one port, such as Boston, but because the broken coastline of Massachusetts and Maine (part of Massachusetts until 1820) contained many inlets, which in that day of small and shallow-drafted vessels sent ships all over the world, including Russia.

[11C] page 265

Boston, as one would expect, excelled in praising Russia’s victories. The day of 25 March 1813 was set aside for a festival to “solemnize the glorious and important events the Almighty has vouchsafed to bring to pass in Russia.” The celebration began at King’s Chapel, where the crowded pews were regaled with prayers, recitations, choruses – the Hallelujah Chorus was particularly well received – and a discourse by the Reverend Dr. James Freeman. (Freeman was a member of the Yankee clergy who were so pro-Russian that Cobbett, the British journalist, called them the “Cossack Priesthood.”)

=-=-=-=-=-

[12] A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky

James F. Hopkins

University of Kentucky Press

1951

[12A] pages 133-134

During the first third of the nineteenth century most of the rope made in Kentucky was spun and twisted by hand and by the use of horse power at one end of the walk. In 1838 David Myerle, formerly of the [ropemaking] firm of Tiers and Myerle, Philadelphia, established upon a new principle a large steam-driven factory at Louisville. The method of manufacture had been invented earlier by Robert Graves of Boston, from whom Myerle had bought the patent right, . . .

[12B] page 160

At last, in 1838, a ropewalk was completed at the Charlestown, Massachusetts, Navy Yard, and the navy began manufacturing its own cordage. Although in its first contracts for hemp the government specified that it be the best Russian fiber, the completion of the national ropewalk set the stage for a resurgence in Kentucky of interest in producing hemp for marine use.

[12C] page 161

In order to encourage him in the venture and to make it remunerative to him, the Department gave Myerle a contract under which he agreed to deliver to the Charlestown Navy Yard by March 1, 1841, two hundred tons of American water rotted hemp, for which he was to receive $300 per ton, a price $91 higher than that being paid for Russian fiber at the time the contract was made.

[12D] page 166

Again he [Myerle in Missouri] made a shipment, of seventy tons on this occasion, to the [Charlestown] navy yard, and again his product was rejected. Further heavy losses on shipments to Boston, New York, and Europe rendered him unable to pay for the crops which he had induced the farmers to raise, and he became discredited in the region where once he had enjoyed great popularity.

[12E] page 168

For more than a decade after the rejection of his fiber at Charlestown, Kentucky was vigorous in its efforts to capture the market for naval cordage, although in their final results these efforts came but little nearer success than had those of David Myerle.

[12F] page 217 [footnote 133]

During the period 1839 through 1843 the ropewalk consumed in manufacturing cordage over 5,000,000 pounds of Russian hemp, almost 400,000 pounds of Manila hemp, and only 66,074 pounds of American.

=-=-=-=-=-

[13] Charlestown Navy Yard

Official National Park Handbook

Produced by the Division of Publications, National Park Service

U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

1995

[13A] 87

Ropewalk page references in the index: 17, 20-21, 45, 49, 50, 67, 72, 83

[13B] page 17

The yard had become more self-sufficient. The boilers for the dry dock pump engines also provided steam for the new sawmill and blockmaking and armorer’s shops. In 1837, the yard’s ropewalk (also steam-powered) and tar house had been completed (see pages 20-21).

[13C] page 83

The country’s only remaining full-length ropewalk (left) was for more than 130 years the sole facility in the Navy manufacturing rope for U.S. warships. Both buildings (not open to the public) await restoration and preservation work as part of the National Park Service’s ongoing efforts to preserve the significant industrial heritage of the Charlestown Navy Yard.